- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- The Andean Coastline Islands: Notes on their Economy and Rites in Pre-Hispanic Periods, Part 2 (Conclusion)

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

International academic cooperation between the Wiese Foundation and Universidad Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul ...

Clothing at El Brujo: footwear ...

To receive new news.

Por: José Ismael Alva Ch.

By: José Ismael Alva Ch.

In the previous installment we saw the economic aspect of the islands and their utilization since pre-Hispanic times. On this occasion we will briefly address the religious attributes of the islands, based on chronicles and archaeological evidence recovered in the XIX century. Finally, we will deal with the case of the Macabí Islands, located off the coast of the Chicama Valley, on the North Coast of Peru. We will review the archaeological materials found on these islands and will detail the ancient activities carried out there.

The myths and ceremonies on the Islands

The ancient Andean peoples considered that the extraction of the resources of the islands should be thanked for and rewarded with rites and offerings; only in this way was the principle of reciprocity honored. From the documentation of the XVI and XVII centuries, we know that, on the central coast, ritual activity on the islands was associated with two main deities: Huamancantac and Urpay Huáchac.

According to José de Arriaga (1621, Ch. V, fol. 31), Huamancantac was known as the “Lord of Huano” with his shrine on the islands of Huaura, in front of the town of Huacho. Offerings were given to this deity when the guano was collected and, on their return to the port, the collectors went on a two-day fast, followed by parties.

To the south, Cristóbal de Albornoz recorded that Urpay Huachac, goddess of birds and fish, had a shrine on the Chincha Islands, where fishermen worshiped her. On her part, María Rostworowski has traced the veneration of this deity in the central and northern highlands of the Andes, considering, in addition, that her cult must have originated in very ancient times (Rostworowski, 1983, p. 86- 87).

The archaeological evidence associated with the islands off the coast seems to reaffirm the sacred treatment of these spaces. Anne Marie Hocquenhem (1987, p. 129) when analyzing the Moche iconography of the hunting of sea lions indicates that “Some scenes represent an island with a temple in which two bodies are lying down and in front of which there is a shaman, as well as offerings ”.

Other archaeological objects widely collected during the Era of Guano (1845-1879) also account for the ritual use of the islands. George Kubler, in 1949, made a first synthesis of the archaeological evidence found on the islands of the Peruvian coast and distributed in different museums in the United States and England. These objects are made up of multiple sheets of gold and silver with human and animal representations and wooden sculptures, among others.

The Macabí Islands

Two islands located 12 kilometers southeast of Punta Malabrigo and 24 kilometers northwest of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex are known as the Macabí islands. Both islands are separated by a narrow natural corridor of 25 meters (Buse, 1975, Volume II, Vol. 2, p. 610).

According to Kubler (1949, p. 36), several wooden sculptures were recovered from the Macabí Islands under 18 meters of guano during the exploitation of this resource in the 19th century. These objects, and others, from the islands were acquired by the British Museum in 1871.

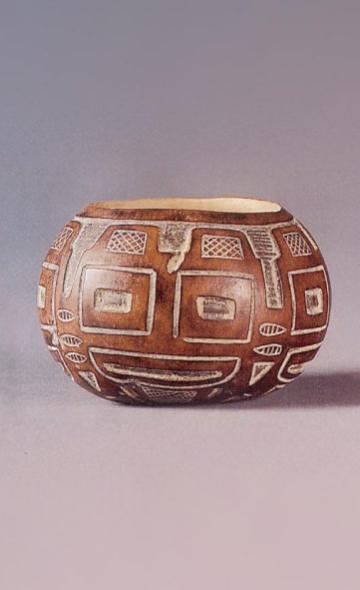

The review of this collection allows us to sustain that the Macabí Islands were subject to the economic and religious activities of the pre-Hispanic societies of the coast. Although most of the objects are in the Moche style, there are fine Inca-style ceramic vessels; which is an indicator of the continuity of its exploitation and the particular attention that this resource received in Tawantinsuyu times.

Among these materials we can recognize fragments of wooden truncheons from the Moche period, which must have served for hunting sea lions. Moreover, the remains of truncheons carefully carved with representations of high-ranking personages were identified, the use of which must have been destined for the execution of ceremonial acts.

On the other hand, in the wood carvings there are representations of male individuals with strappings. These sculptures of clear Moche filiation, remind us of the scenes of bondage and procession of prisoners depicted in the ceramics and mural art of the Huaca Cao Viejo and Huaca de La Luna, with the practice of violence being a recurring activity in Moche ceremonies.

The discovery of spondylus in Macabí refers to its placement in offerings. We must remember that these red valves from warm waters were highly valued in the Andes, in such a way that there were special exchange circuits to obtain and distribute them. Its use in Andean ceremonies is widely known and there are extensive studies in this regard, so the presence of spondylus in the Macabí Islands reaffirms the religious character of the activities carried out on them, probably related to the extraction of guano.

As we can see, the veil of rituality hides behind it the production processes of Andean societies. The level of importance of the islands transcended the people who lived on the coast, since guano was required to also fertilize the fields of the mountains, guaranteeing good harvests. The sacralization of the islands through myths and ceremonies is a consequence of the great importance of these economic spaces in the life of the peoples of ancient Peru. At this point, unraveling religious discourses is a necessary task, as it should guide us to understand social behavior and economic and power structures, as well as their particularities and contradictions in the vast territory of ecological diversity that the Andes represent.

Bibliography

• Arriaga, J. (1621). Extirpation of the Idolatry of Pirú directed to King Nuestro Señor and his Royal Council of the Indies. Lima: Geronymo de Contreras, Book Printer.

• Buse, H. (1975). Maritime History of Peru. Prehistoric Epoch. Volume II, Volume 1 and 2. Lima: Institute of Historical-Maritime Studies of Peru

• Hocquenghem, A. M. (1987). Mochica iconography. Lima: Pontifical Catholic University of Peru.

• Kubler, G. (1948). Towards absolute time: Guano archeology. Memoirs of the Society for American Archeology, 4, 29-50.

• Rostworowski, M. (1983). Andean Power Structures. Lima: Institute of Peruvian Studies.

Researchers , outstanding news